From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- Not to be confused with the anti-nuclear Plowshares Movement.

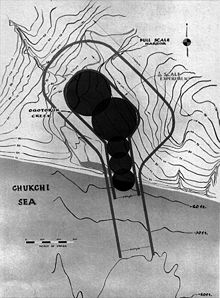

The 1962 "Sedan" plowshares shot displaced 12 million tons of earth and created a crater 320 feet (100 m) deep and 1,280 feet (390 m) wide

Despite successfully demonstrating non-combat uses for nuclear explosives, (i.e., for rock blasting and stimulation of tight gas), negative impacts from Project Plowshare’s 27 nuclear projects led to the program's termination in 1977, due in large part to public opposition.[1] These consequences included tritium-contaminated water and the deposition of fallout from radioactive material being injected into the atmosphere, which led to an increase in environmental levels of radioactivity across the United States.[1]

Contents

- 1 Proposals

- 2 Plowshare testing

- 3 Plowshare tests

- 4 Negative impacts and opposition

- 5 See also

- 6 References

- 7 External links

Proposals

Proposed uses for nuclear explosives under Project Plowshare included widening the Panama Canal, constructing a new sea-level waterway through Nicaragua nicknamed the Pan-Atomic Canal, cutting paths through mountainous areas for highways, and connecting inland river systems. Other proposals involved blasting underground caverns for water, natural gas, and petroleum storage. Serious consideration was also given to using these explosives for various mining operations. One proposal suggested using nuclear blasts to connect underground aquifers in Arizona. Another plan involved surface blasting on the western slope of California's Sacramento Valley for a water transport project.[1]Project Carryall,[2] proposed in 1963 by the Atomic Energy Commission, the California Division of Highways (now Caltrans), and the Santa Fe Railway, would have used 22 nuclear explosions to excavate a massive roadcut through the Bristol Mountains in the Mojave Desert, to accommodate construction of Interstate 40 and a new rail line.[1] At the end of the program, a major objective was to develop nuclear explosives, and blast techniques, for stimulating the flow of natural gas in "tight" underground reservoir formations. In the 1960s, a proposal was suggested for a modified in situ shale oil extraction process which involved creation of a rubble chimney (a zone in the oil shale formation created by breaking the rock into fragments) using a nuclear explosive.[3] However, this approach was abandoned for a number of technical reasons.

The first PNE blast was Project Gnome, conducted on December 10, 1961 in a salt bed 24 mi (39 km) southeast of Carlsbad, New Mexico. The explosion released 3.1 kilotons (13 TJ) of energy yield at a depth of 361 meters (1,184 ft) which resulted in the formation of a 170 ft (52 m) diameter, 80 ft (24 m) high cavity. The test had many objectives. The most public of these involved the generation of steam which could then be used to generate electricity. Another objective was the production of useful radioisotopes and their recovery. Another experiment involved neutron time-of-flight physics. A fourth experiment involved geophysical studies based upon the timed seismic source. Only the last objective was considered a complete success. The blast unintentionally vented radioactive steam while the press watched. The partly developed Project Coach detonation experiment that was to follow adjacent to the Gnome test was then canceled.

Over the next 11 years 26 more nuclear explosion tests were conducted under the U.S. PNE program. Funding quietly ended in 1977. Costs for the program have been estimated at more than (US) $770 million.[1]

Natural gas stimulation experiment

The final PNE blast took place on 17 May 1973, under Fawn Creek, 76.4 km north of Grand Junction, Colorado. Three 30 kiloton detonations took place simultaneously at depths of 1,758, 1,875, and 2,015 meters. It was the third nuclear explosion experiment intended to stimulate the flow of natural gas from "tight" formation gas fields. Industrial participants included the El Paso Natural Gas Company for the Gasbuggy test; Austral Oil Company; CER Geonuclear Corporation for the Rulison test; and CER Geonuclear Corporation for the Rio Blanco test.If it was successful, plans called for the use of hundreds of specialized nuclear explosives in the western Rockies gas fields. The previous two tests had indicated that the produced natural gas would be too radioactive for safe use. After the test it was found that the blast cavities had not connected as hoped, and the resulting gas still contained unacceptable levels of radionuclides.[5]

By 1974, approximately $82 million had been invested in the nuclear gas stimulation technology program. It was estimated that even after 25 years of gas production of all the natural gas deemed recoverable, that only 15 to 40 percent of the investment could be recovered.

Also, the concept that stove burners in California might soon emit trace amounts of blast radionuclides into family homes did not sit well with the general public. The contaminated well gas was never channeled into commercial supply lines.

The radioactive blast debris from 839 U.S. underground nuclear test explosions remains buried in-place and has been judged impractical to remove by the DOE's Nevada Site Office.

The situation remained so for the next three decades, but a resurgence in Colorado Western slope natural gas drilling has brought resource development closer and closer to the original underground detonations. By mid-2009, 84 drilling permits had been issued within a 3-mile radius, with 11 permits within one mile of the site.[6]

No comments:

Post a Comment